Part I — The Dawn of Patent Analytics and Why We Need A Better Approach

The concepts of patent quality and value have been around for as long as patents themselves. Nevertheless, they still seem to fail at providing what patent holders need: a solution to help them manage their portfolios. On top of that, the number of patents filed every year is continuously increasing, adding to the confusion. To solve this problem, we might need to reconsider the traditional idea of patent evaluation entirely. Before finding out, let’s take a look at the current approach and the story behind it.

Patent systems were established with the ultimate goal of fostering economic growth and technological developments by rewarding those individuals — the inventors — who are willing to share their wisdom with society.

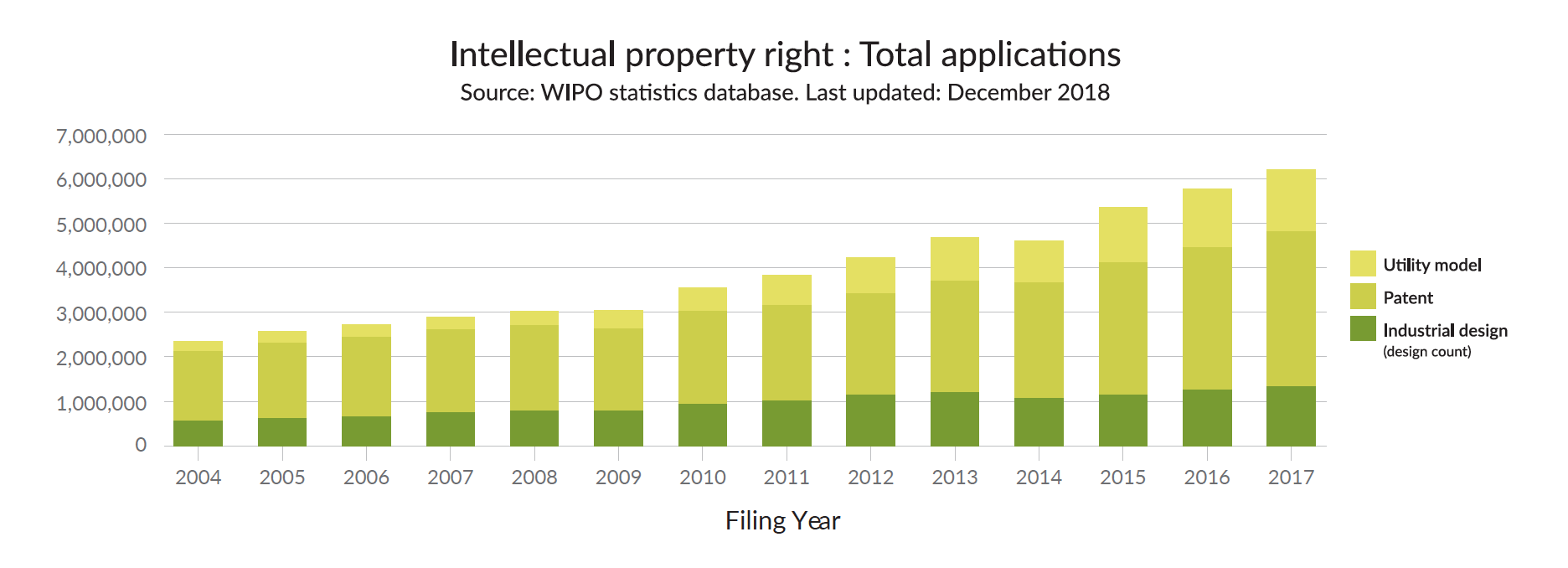

Just as technology and global economies have boomed over the decades, so has the resulting number of patent filings. A look at the statistics from the World Intellectual Property Organization should give us a glimpse into this trend:

There’s certainly no doubt that such a rich disclosure of knowledge brought a significant number of benefits to our day-to-day life. The rapid pace at which the phenomenon occurred, however, introduced several downsides.

As an attempt to fix this stagnant situation, the first online patent databases appeared in the 90s: even though they provided accessible and consolidated patent data to everyone for the first time, the overall data quality was poor and lacking in depth.

The issue of data utilization, therefore, was there to stay and without comprehensive data to rely on, patent intelligence shifted its focus to quantity-based evaluations.

This approach, however, has its grounds on the wrong assumption that “all patents are created equal,” making it a way less “intelligent” form of evaluation.

As well-known by practitioners in the patent field, the mere quantity of patents in a portfolio is an extremely weak indicator of its actual strength.

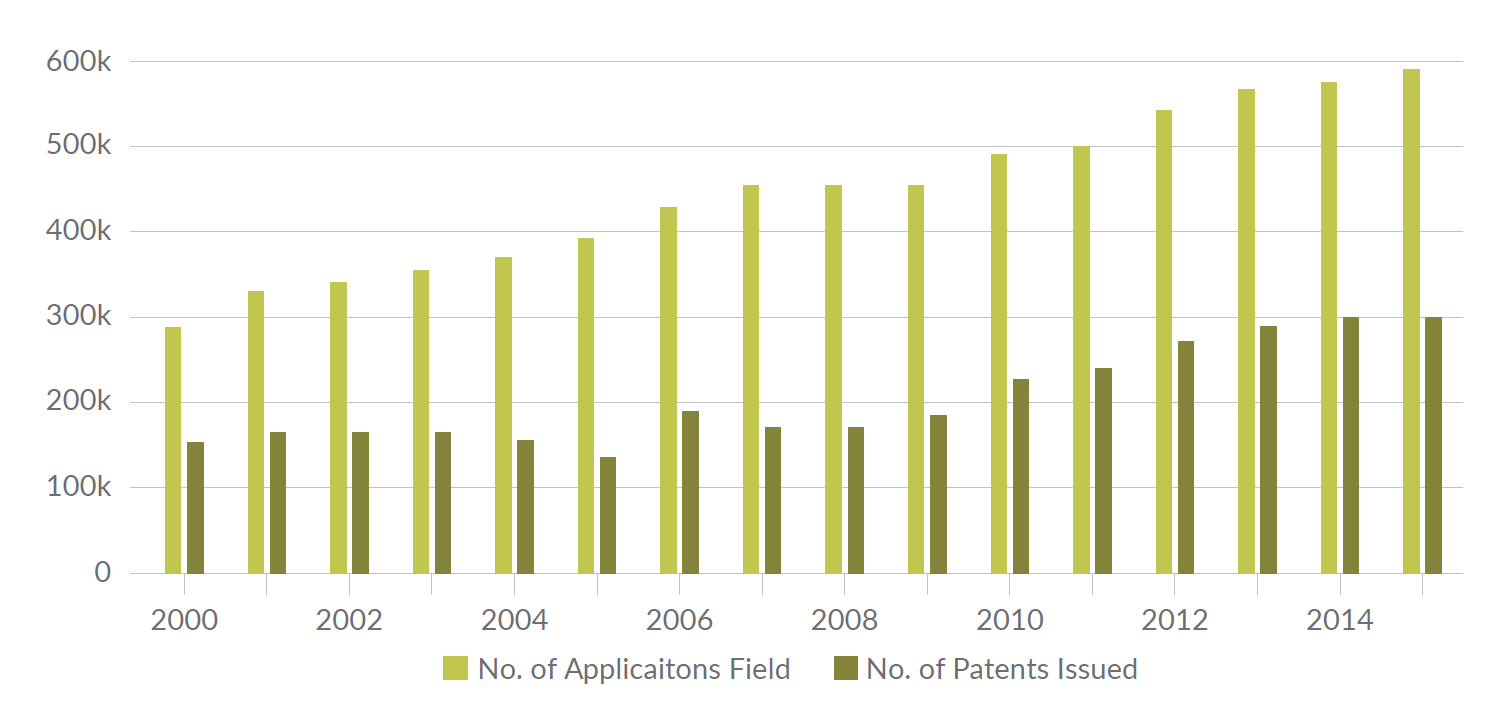

A higher number of patent filings may not necessarily result in more innovations successfully going through the patent office’s scrutiny for novelty and non-obviousness:

Above all, issues in terms of data access, aggregation, and utilization, which over time made it more and more difficult for patent professionals to identify quality patents.

Similarly, abundant portfolios may not directly result in a higher value for the holder: most patents, in fact, create no value at all and remain dormant until they are abandoned, lapsed, or expired.

To sum it up, the quantity-based patent analytics, by relying on the “all patents are created equal” myth and by making use of underutilized patent data, resulted in the assumption of “quantity equals value”, leading practitioners away from facts and valuable insights.

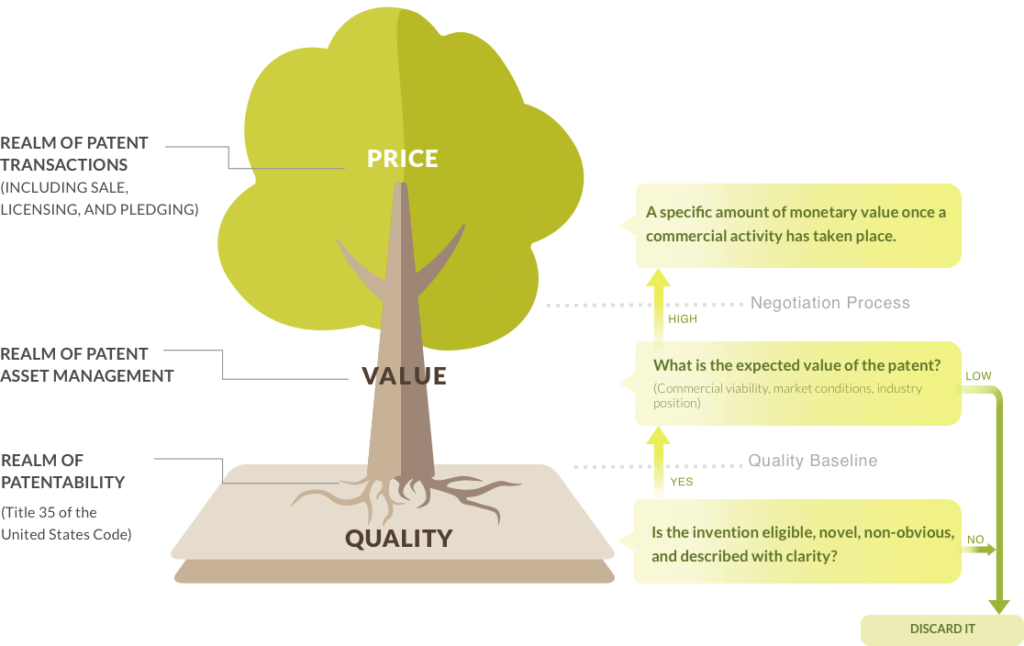

The three pillars of patent evaluation: Quality, Value, and Price

Before introducing a better way to value patent assets, we should take a moment to discuss the three concepts that patent practitioners have introduced over the years to attempt at dealing with the aforementioned myth.

Quality

The notion of quality is tied up with the patentability requirements stated in Title 35 of the United States Code, in particular at Section 101 (utility and eligibility), Section 102 (novelty), Section 103 (non-obviousness), and Section 112 (adequately described): if a claimed invention is eligible, novel, non-obvious, and described with clarity, it is deemed to have at least a baseline (or minimum) of quality.

Quality patents must feature a claim language that is carefully crafted to ensure accuracy and logic, as this will broaden their scope and consequently slim down the chances for competitors to design-around.

In spite of the slightly different definitions, the concept of patent quality is widely accepted as being the foundation of value and price.

Value

Should a patent be practiced without authorization, its owner may decide to enforce it before a court. This confidence in patent enforcement provides the foundation of patent transactions, such as sale, licensing, and pledging.

The expected value earned from these transactions is widely agreed as being the commercial or monetary value of the patent as an asset.

We should point out that a heavily researched and well-written patent may meet all the patentability requirements but have very little value: the covered invention, for example, might be outdated or related to an obscure technology that only the inventor is interested in developing.

Patent value — either realized from enforcement, transaction, or other commercial practices — goes well beyond the four corners of a patent by taking into account commercial viability, market conditions, and industry position.

For patent holders who are managing patent assets, the patent value doesn’t necessarily need to be a specific monetary figure: at this stage, it is far more important for them to understand the potential monetary return of the patent, especially when deciding whether to maintain, activate, or discard it.

Price

Once a commercial activity takes place, both parties need to determine a specific amount for the monetary value: this is when they resort to patent price.

The price of a patent is generally formulated through negotiation or litigation on the basis of the cognition that each party has with regard to the value of the patent at issue.

It is the concept of patent quality that determines whether a patent can be deemed as an asset or not according to its validity and enforceability.

It should be clear by now that, although practitioners may advocate different approaches, it is widely agreed that patent quality, value, and price are separate — yet highly dependent on one other — factors.

These factors plays an important role in patent evaluation. We will further discuss about the challenges in traditional patent evaluation and how patent quality, value and price can make the patent evaluation more effective.

Traditional patent evaluation methods and the challenges faced

The concept of patent price and the corresponding valuation models were first developed for accounting and financial reporting purposes.

These valuation models — which were originally developed to meet the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) — were later leveraged in decision-making and practice of patent asset management and transactions.

Traditional evaluation methods used for asset management and transactions typically relied on the judgments of the stakeholders (i.e., inventors, applicants, agents, and examiners), based on their knowledge, experience, and the particular case they were facing.

Later on, different aspects of the market, technology, and patent practices started being taken into consideration.

However, due to the insurmountable costs associated with the time needed to perform such an evaluation, this traditional method could only really be used on a case-by-case basis and performed for specific patents on specific decision points.

To increase the speed and efficiency of patent evaluations, computer algorithms were developed to emulate the evaluation methods used by patent practitioners, such as the work by CHI Research in the 90s.

The research was conducted for various purposes, including patent management, patent transactions, and patent landscaping.

Many patent data and analytics service providers also created evaluation indicators based on their own understanding of patent quality, value, and price.

Utilizing assumptions, foundations, and key parameters formulated as secret “recipes”, these early approaches and indicators often had difficulty overcoming several significant challenges.

Their main pain point is that they often aggregate multiple distinct elements into a single indicator, which makes such an indicator vague and unclear.

Whether such an indicator reflects the true patent value or not, it often provides no reason as to why the patent is of any value: to establish it, each distinct element or “recipe” used by patent practitioners to evaluate patents must be transparent.

However, unsurprisingly, most practitioners are unwilling to divulge the secrets of their trade.

Even if the “recipes” are published, proving the relevance of this aggregation of multiple considerations still remains problematic, simply because there is no single meaning for the indicator.

This lack of consistency in interpretation has caused controversy among patent professionals of different backgrounds and experience levels, ultimately leading clients astray.

In contrast to the aggregated indicator approach, some vendors or researchers set up simple parameters, such as the number of forward-citations or the number of family members for evaluation.

These simple parameter approaches, however, have forced users to return to their offline assessments by aggregating up the parameters by themselves, since it is even harder to tell the relevance and weight of the contribution of each parameter.

As a result, returning to case-by-case evaluation happens as a matter of course.

A more meaningful and useful method for patent evaluation

With the emergence of big data and machine learning technology, data modeling for predicting the tendency of a specific event involving patents has now become possible.

As long as the big data provides sufficient information for machine learning to extract useful patent data, this technology may provide an analysis that resembles patent value.

There are researchers and service providers who have been trying to leverage machine learning technology to uncover the strength, or other indexes, of patent data.

However, these indexes either confuse the fundamental concept of patent quality and patent value or ignore patent quality altogether.

To address such issues, InQuartik developed a more meaningful and useful method to evaluate patents via its Patentcloud platform, which includes the exclusive and proprietary Patent Quality and Value Rankings.

By separating these two indicators, users can leverage the Patent Value Ranking and the Patent Quality Ranking independently for different decision points in the patent life cycle, and even obtain patent intelligence for insights, such as patent clearance, patent portfolio, patent landscape, and patent due diligence for M&A and investment purposes.

Patentcloud’s Patent Value Ranking focuses on reflecting the relative tendency of a patent to be practiced or monetized after its issuance.

The Patent Quality Ranking focuses on indicating the relative eventuality of prior art references being found for a patent, which can threaten its validity.

These rankings are not meant to replace a case-by-case evaluation of a specific patent but are instead intended not only to serve as an effective filter or additional dimension when dealing with patent data but also to provide actionable intelligence.

To check out the other articles in the series, follow the links below:

Download our white paper Patent Quality and Value Rankings to discover how the Patent Quality and Value Rankings work in detail.