- Principle 5: Geographic balance.

- Principle 6: Time balance.

- Principle 7: Identify and fill holes in coverage.

- Principle 8: Time management, including divestment.

- Principle 9: Establish criteria for measurement.

- Principle 10: Place the patenting function within the organization.

In part one of our article under the same heading, we asked the author of the book “Patent Portfolios – Quality, Creation, and Cost”, Larry M. Goldstein for his top ten principles that make excellent patent portfolios, and revealed the first four.

If you haven’t already read part one I highly suggest you do, as this follows on from it. In part two, we learn the remaining six principles that make up excellent global patent portfolios.

The principles of a great patent portfolio – continued

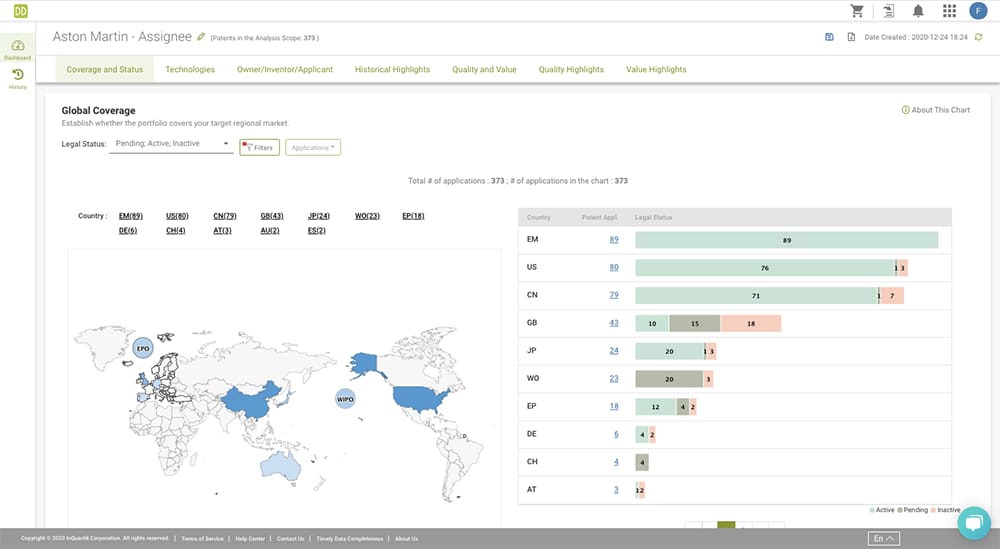

Principle 5: Geographic balance.

A good patent portfolio needs to be well balanced geographically, with at least three geographic markets taken into consideration, and with the US being one of those three (see image below).

As the main market for ICT technology and products, patent protection in the US is critical if the owner of the portfolio aspires to be a worldwide player.

Many companies want patent protection in their home country. This is often appropriate, since it deters disruption in a main location of activity. Conversely some countries are not known for strong patent enforcement, and in such countries, the need for local protection may be less pronounced.

In addition to the US and home market, it often makes sense to file in the company’s most significant revenue locations as this not only protects local efforts of the company, but also provides patent protection for the company’s customers and distributors.

Some companies like to have patents registered in the countries in which major competitors are based or are strong in the market. The rationale is that such patents deter threats of litigation from competitors. However, the costs for such protection can be high and sometimes unjustified, unless there is a real possibility of engaging in patent litigation against the competitors.

So, how does a company decide which geographic markets to emphasize in its patenting activities? Focusing efforts is critically important, especially for ICT patents. Owners of patents for new drugs often register worldwide patent protection costing several millions of dollars per patent. But, the cost of worldwide protection is too high for most ICT patents.

Here are some considerations that ICT companies use when determining geographic focus:

Market importance: Importance of the geographic market to the company.

Cost: Cost covers time, effort, and money, in obtaining effective patent protection in the specified country. Although the cost of obtaining patent protection in the US is high, other countries like Japan and Europe can often work out higher after filing and translation fees.

One method for reducing these costs is to utilize the “Patent Prosecution Highway”, but even with these programs, international protection remains expensive and must be planned in advance.

Enforceability: It is assumed that patents are equally enforceable in all countries, but this is not true. For example, patents for software or business methods and processes are enforceable in the US, but will likely be an uphill battle in Europe and are unlikely to be recognized at all in some Asian countries.

Chinese courts have a reputation for being highly resistant in enforcing patents held by non-Chinese nationals.

Timing: If a chain of priority is preserved, later filings in multiple countries may all rely for their priority date on an original filing in one country. Nevertheless, despite maintenance of early priority date across multiple countries, the specific order in which applications are filed in various countries is of great importance, for two reasons.

First, applications that are filed earlier will very likely be granted earlier than applications that are filed later. Second, the “tone” or character of the application is very often set by the original filing. For example, the special form of patent claim known in the US as the “Jepson claim” (known in Europe as the “two-part claim“) almost never appears in patents derived from an original US filing, but appears frequently in those from an original European filing.

Extensive international filing quickly becomes very expensive. In order to control cost and achieve geographic balance, a company needs a clear understanding of the costs and benefits from filing applications in various countries, and a well thought out plan to achieve the results at a reasonable cost.

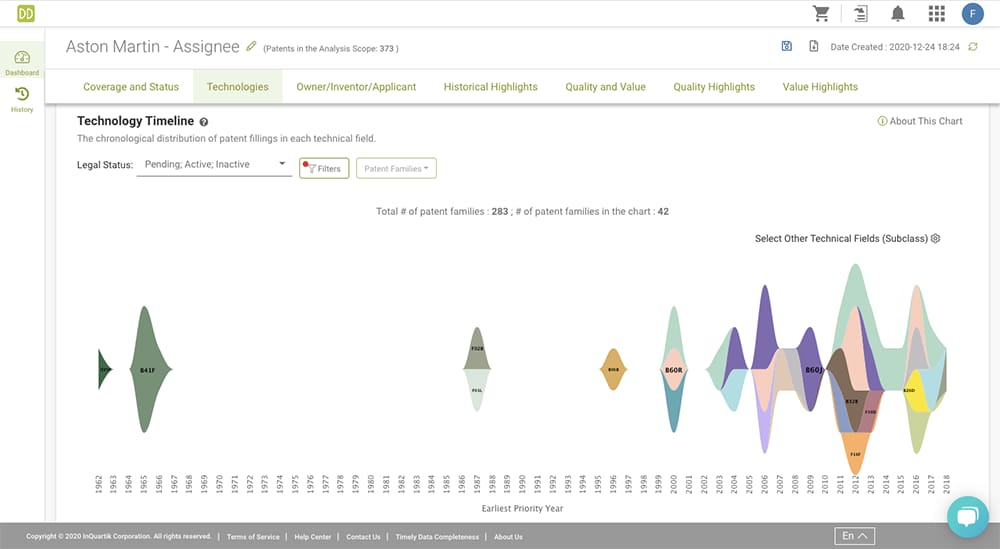

Principle 6: Time balance.

A good patent portfolio is balanced over time. All companies go through several stages during their life, particularly companies that are heavily focused on technology (see image below).

The initial stage is very R&D intensive with major technical advances, followed by a middle stage with decreased R&D work, followed by a decline phase where R&D is reduced significantly. Patent activity needs to match these stages.

In the beginning, whilst the company is investing heavily in R&D the company also needs to invest heavily in patents. This investment is not only money, but also the time of senior R&D people. Resources will need to be balanced, particularly in the early stages as this is when most innovations and technical contributions are likely to happen.

These innovations must be patented early, as failure to do so cannot be recovered years later. In the event that costs are a problem, the investments can be limited through various techniques. These are:

- Focusing only on the highest technical contributions.

- By only producing a small number of outstanding patents.

- Intelligent use of patent continuations to put off much of the cost in the US.

- Using the international application known as PCT to put off international investment.

- Using area applications (such as European Patent Office rather than multiple European countries) to delay international investment.

Despite cost-saving exercises, significant investment of time and money must be made in patents at the early stages of a company’s life. This is not only true for an entire company but also for a new product line or new technology within a company. For companies to stay ahead in the market they must perpetually reinvent themselves with new technologies, products, and innovation, so patent investment remains critical throughout.

Principle 7: Identify and fill holes in coverage.

Management of a portfolio requires that holes in the portfolio are constantly identified and filled in. These holes may be caused by expiration of patents over time, by changing needs, prior errors, or just simply allocating more resources to patent portfolios and IP. Whatever the reason is, it must be proactive and ongoing.

There are only two ways to fill holes in a portfolio — prepare and prosecute your own application, or buy existing patents. Both have pros and cons. Whilst creating and preparing your own patent application gives more control, the compromise is the delay in the time taken for it to be granted — typically 3-5 years at most.

The only guaranteed way to quickly fill a hole in a patent portfolio is to identify existing patents owned by others, and purchase them. This method allows companies to select exactly what is needed, and can be a quick solution, but will inevitably cost a lot more.

Principle 8: Time management, including divestment.

For a global patent portfolio to maintain value, the patenting activities must be an ongoing and evolving process, as patents expire over time. Unmaintained patent portfolios gradually decline in quantity and quality as these patents expire.

If a company is to remain with a competitive edge and continuity of its patent coverage, then applying resources to its patenting activities over time is key. Most companies engage in bursts of patenting activity for a small period of time and then stop for a while before reviewing again, and this cycle is detrimental to the future progression of the business.

Almost in every portfolio a very few patents create the large majority of the value, either for aggression (generating licensing revenue or to inhibit the R&D efforts of competitors), or for defense (to deter patent lawsuits by competitors and to obtain for freedom to operate). When those main drivers of value expire, the company has reached a decision point.

On the other hand, there are also patents that have little to no value, or use, within the portfolio. This could be for a number of reasons which include; the patent suffering defeat in litigation, a change of law, old technology, or that the company wishes to focus efforts in other areas. Patentcloud’s Due Diligence platform allows the user to distinguish between the higher value and lower value patents (see images below).

Maintaining patents costs money, primarily in maintenance fees — for an explanation of what patent maintenance fees are, read our article titled “An Inventor’s Guide to Understanding Patent Maintenance Fees”, therefore, a company should focus on current and future activities and divest old patents through either sale or abandonment.

Principle 9: Establish criteria for measurement.

Corporate strategy comes first, then patent strategy as a support to corporate strategy, and then measurement criteria for determining whether the patenting efforts are achieving their intended goals.

The specific criteria depend on the specific goal, and if the company is pursuing multiple goals in its patenting efforts, the portfolio will be judged by suitable criteria for each goal.

So, if the goal is to generate income by licensing or litigation, then revenue generation will be measured over time. Or there will be a comparison of revenue generation versus the total cost to generate the revenue.

Another criteria could be, how effective is R&D in creating value? One measure is the number of new products and services developed over time, or the number of patent applications and patents generated over time, or another measure is the amount of licensing revenue as a percentage of R&D over time.

One criteria that is difficult to judge is how effective is the patent portfolio in inhibiting competitors and generating value by a predominant position for a particular innovation? However, if done correctly, can create tremendous value for the company.

Principle 10: Place the patenting function within the organization.

Where should the patenting function fit within the organization? Who should have control of it, and inevitably be responsible for it? This is a question that needs careful consideration.

Different departments within companies will have different attitudes towards patents and how the portfolios are managed. There are four options which are used by various companies.

First, placing patents within the legal department. This makes sense, as patents are a legal concept, and are created by legal professionals who work closely with inventors. Also, the legal department will be the ones involved with any litigation attempts by competitors or the company itself, and this department will have the most knowledge of recent legal changes affecting patents and their industry.

Second, placing patents under the Chief Technology Officer. The CTO monitors the success of R&D efforts, and success with patent creation is one measure of R&D success. The CTO is most likely to understand the technical implications of each invention, and the department best placed within the company to determine priorities of technical importance.

Third, placing patents under the VP of Business Development. Although this might not seem like the most obvious choice, as the business development department are not likely to understand the legal or technical implications of patents, this department may be in charge of licensing intellectual property, creating joint ventures and joint R&D efforts, and merger and acquisition activity, all of which involve patents. This placement makes more sense for monetizing and revenue and business generation.

Fourth, placing patents and patent responsibility within the Strategic Business Unit responsible for creating technology, developing products and generating revenue from the products.

The advantages of this placement is that SBU managers are likely to have the best understanding of the technology protected by the patents, the best understanding of the specific business implications of the patents, and the most incentive to use patents in every possible way to meet the financial goals of the SBU.

The disadvantages of this placement is that SBU managers will likely have no legal expertise, will probably be less interested in the long-term technical implications of the patents, and will likely be unable to prevent duplication of technical and patenting efforts with other SBUs within the company.

It is of course possible to include various combinations of the four placements listed above. Split placement of the patenting functions and responsibilities helps maximise the natural expertise of different groups within the company, but creates coordination problems. However, patenting must be placed in-house to fulfil the goals of the patent function, and of the corporate strategy.

The use of technology in global patent portfolio management

As mentioned in part one, the use of Patentcloud‘s Patent Search and Due Diligence enables the user to make educated decisions based on the metrics of the patent data for aspects such as, quality rating of the patent, value rating of the patent, patent family, date of expiration. For a free seven day trial, sign up here (no credit card required).

Patent Vault is another product under Patentcloud which utilises the patent data, enabling perfect global patent portfolio management. The platform simplifies the management of your entire global portfolio in one console, making sure to never miss the maintenance fees again, and is accessible at the touch of a button, for potential investors to view.

For a free seven day trial, sign up here

no credit card required

The “Ten Principles” outlined in this guide are taken, in full, or, in part, from the book titled “Patent Portfolios – Quality, Creation, and Cost”, written by US Patent Attorney Larry M. Goldstein who is based in Tel Aviv, Israel. “Patent Portfolios – Quality, Creation, and Cost”, and Goldstein’s other titles “True Patent Value”, and “Litigation-Proof Patents”, are available to purchase in English and Mandarin from the website www.truepatentvalue.com.

All quotes used are with the permission from the author Larry M. Goldstein.