In this article:

- What is claim construction?

- What is the purpose of claim construction?

- Who is responsible for conducting claim construction?

- The claim construction process — how it works

- Approaches to claim construction

- Markman hearings — the formal interpretation of claim construction

- What is a claim chart?

If you are following patent litigation cases, you must have come across the term “claim construction” from time to time. In this article, we will go over the basics of claim construction, along with an overview of claim construction charts, both important cogs and wheels of patent litigation.

What is claim construction?

Contrary to the term “construction,” claim construction is not the act of “constructing” a new claim in a patent. We call this process “drafting” claims. Claim construction is the act of reviewing and interpreting the claims of an existing patent for further comparison with an infringing product or process. You can think of it as “reconstructing” patent claims into more understandable terms.

As claim construction examines the evidence of the patent at issue, claim construction is case-specific for each case and any interpretation cannot be used interchangeably.

What is the purpose of claim construction?

Although claim construction is mainly seen and used in infringement lawsuits, the act itself can also be used for various non-litigation scenarios. We can roughly divide the purposes of claim construction into litigation issues and non-litigation issues.

- Litigation issues

Claim construction is regarded as the most fundamental issue in any infringement litigation. It interprets a patent’s claims and defines the scope of a patent, setting the grounds for the case. It can also be a tool to use pre-litigation. For instance, you could write up an informal claim construction and approach infringers to threaten to sue.

- Non-litigation issues

For monetization, such as selling/acquisition and licensing (especially from the licensee viewpoint), claim construction is important in examining the scope of the patent and its relation to potential or existing products. If you were planning to license a patent from a company, you would need to understand what and how much their patent claims covers. This also works if you are performing patent landscaping or market probing by looking at a competitor’s patent scope and their product coverage.

Who is responsible for conducting claim construction?

For litigation cases, claim construction is done by the court, usually by the judge, sometimes by a jury. In principle, the judge is responsible for interpreting the law (law issue), and the jury is in charge of finding the facts (fact issue). However, this law/fact issue is still under debate. Many scholars and experts advise that the judge should be responsible for claim construction as jury decisions lead to a high rate of appellate cases. And indeed, most claim construction is overseen by the presiding judge. Often than not, preliminary claim constructions are also done by the attorneys of each party. Sometimes, the judge will review the different versions of claim construction produced by each party when determining infringement.

Informal claim constructions can be done by anyone, but we advise you to have patent attorneys do the job, especially for legal or business-related matters.

The claim construction process — how it works

There are two major steps to this process:

Step 1. Interpreting the claims in the patent

Step 2. Comparison of the claims with the alleged infringing product or process

Let us accompany our imaginary Judge MayKleer in working through claim construction.

Step 1 Interpreting the claims

Judge MayKleer must first understand the patent at issue — what the claims specify and the scope. He does this by examining the following in order:

1. Determining the viewpoint — in the U.S., this is to determine the person having ordinary skill in the art (PHOSITA). Judge MayKleer must establish “who” the PHOSITA is and what level of skill he/she has. If the patent at issue claims a gadget that detects gas leaks in a space shuttle, the PHOSITA would have to be knowledgeable in spaceship engineering and familiar with any related prior art. If the gadget is for detecting gas leaks from gas stoves, then the PHOSITA description and level of skill would be much different, probably someone who is a kitchen appliance mechanic or designer.

However, in China, this is a bit different. The PHOSITA is not determined case-by-case. That person is already presumed to have all relevant skills and omniscient knowledge of all relevant prior art for all cases. China’s patent examination considers another factor — addressing a “technical problem.” So, Judge MayKleer’s law school classmate, Judge Gaodong in China must determine what technical problem the patent at issue is addressing instead.

2. Clarifying uncertain terms — if there are any unclear terms in the claims, Judge MayKleer considers them in the context of:

- the wording, or language of the claims, usually “the ordinary and customary meaning” of such terms. Judge MayKleer can also refer to dictionaries, if needed, to help define the terms. If the gas leak detection patent had a claim stating that gas is detected through acoustic measurement, Judge MayKleer may clarify the term “acoustic” by paraphrasing it as “sound” measurement.

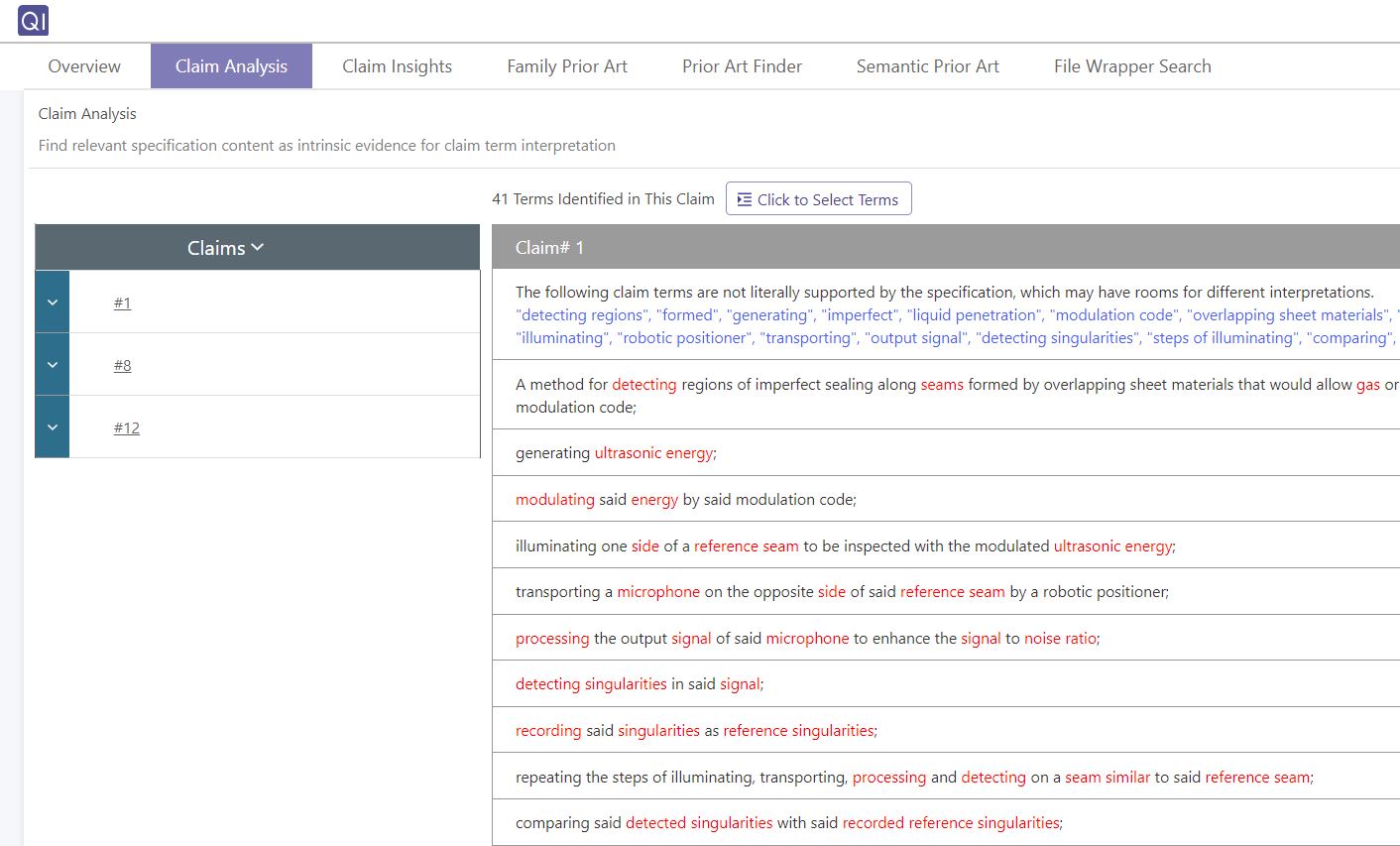

- with regards to the specification. Judge MayKleer feels that the term “sound measurement” is too broad and unclear, so he goes through the specification to see if the patentee had mentioned or expressly defined the term in the patent. To do this, he uses the Claim Analysis function in Quality Insights to cross-search for the keywords “acoustic” and “measurement” in the specification. After finding the relevant paragraphs in the 20 page-long specification, Judge MayKleer deduced that “acoustic measurement” was mentioned by the patentee as measurements including different measurements for sound frequency, sound intensity, vibration velocity, and more. (This claim term is apparently way too broad to have gone past the PTO examiner, but we will let this imaginary patent slide).

- other evidence. Judge MayKleer will also review the patent’s prosecution history, expert testimony, inventor testimony, technical articles, treatises, etc. to better understand and interpret the claims in the patent. Taking expert testimony as an example, Judge MayKleer may need to confirm the ordinary skill of-the-art level with an expert in gas leak detection for spaceships (or kitchen appliances), or he may need a scholar to explain how vibration frequencies are measured. He may also ask the inventor to explain the invention to him or a jury.

“In common use, almost every word has many shades of meaning, and therefore needs to be interpreted by the context.”

– Alfred Marshall, “Principles of Economics”

Step 2 Comparison of the claim construction

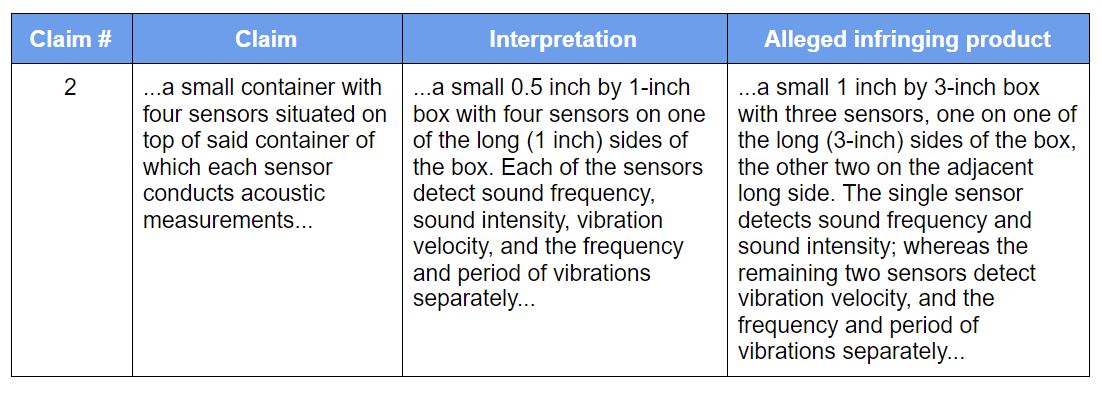

Now that Judge MayKleer has a clear interpretation of all the patent’s claims, he must now compare this paraphrased version to the accused infringing product (or process). Here is a part of this claim construction:

So now, what Judge MayKleer needs to do is to ascertain if the alleged infringer infringes upon a valid patent. Does the alleged infringing product infringe the patent with three sensors that make four measurements? Is the different sized box infringing on the patent? Does the patent claim too broadly to be valid?

We will leave these issues for Judge MayKleer to ponder over.

Approaches to claim interpretation

Before continuing, let us take a peek into the different approaches courts currently take to interpret claims.

- Intrinsic/Extrinsic approach — this approach first examines intrinsic evidence of the patent at issue, including the patent itself (claim language and specification), foreign counterparts of the patent, prior art citations, and prosecution history. Afterward, if needed, extrinsic evidence is then reviewed. This would include expert testimony, inventor testimony, and other documents (dictionaries, technical articles, treaties, etc.). Intrinsic evidence is mainly regarded as the principle in claim construction, and its significance overweighs that of extrinsic evidence. Nevertheless, this is also a case-specific issue and is up to the court to decide the intrinsic/extrinsic interpretation ratio.

- Holistic approach — this approach has no clear methodology, and an interpretation is made by weighing all related evidence. This is a fairly new approach, as new technologies and cases are becoming ever more difficult in interpreting.

- Dictionary-first approach — this is an approach that uses the “heavy presumption” that the patent’s definition of claims is the correct or proper meaning, and a dictionary can define the claim’s ordinary meaning. This approach is no longer in use, yet it is worth mentioning as it is now a method used in claim construction as we saw previously in determining unclear terms.

We see much debate and review of how to conduct claim construction over the years, and to date, there is no best method yet. There are pros and cons to the intrinsic/extrinsic approach and holistic approach, but both are not perfect. The intrinsic/extrinsic approach may be too rigid in some cases as it limits the scope of interpretation, and the holistic approach too ambiguous. Currently, the best way may be to use the intrinsic/extrinsic approach with a dash of the holistic approach.

Markman hearings — the formal interpretation of claim construction

Also called a claim construction hearing, a Markman hearing is a pretrial which sets the official interpretation of a patent in an infringement lawsuit. The timing may vary depending on each district court. Some district courts, such as the California Northern District Court, set Markman hearings before the actual trial, which may encourage a settlement. Others, on the other hand, may be timed nearing the conclusion of a trial.

What is a claim chart?

As we saw in Judge MayKleer’s case, a claim chart is a chart used to analyze patent claims and for comparison purposes. A claim chart comprises at least two columns, with the claims deconstructed into elements in each row. The content and number of the right columns can vary from the interpretation or interpretations, alleged infringing product or process, to further analysis.

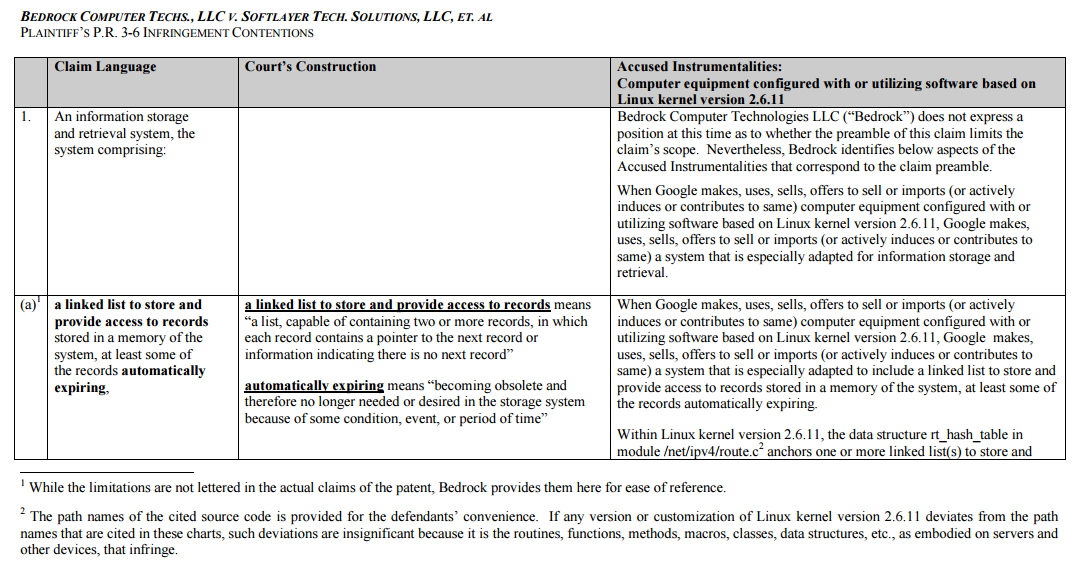

A claim chart done by the court for infringement litigation is used as the grounds for a case. These charts are confidential and extremely difficult to come by. Even in public opinions, the chart itself is omitted because of the sensitive information that will appear in the chart. For instance, a chart may list the original source code of the software which should not be released to the public. Here is an example of a claim chart used in litigation:

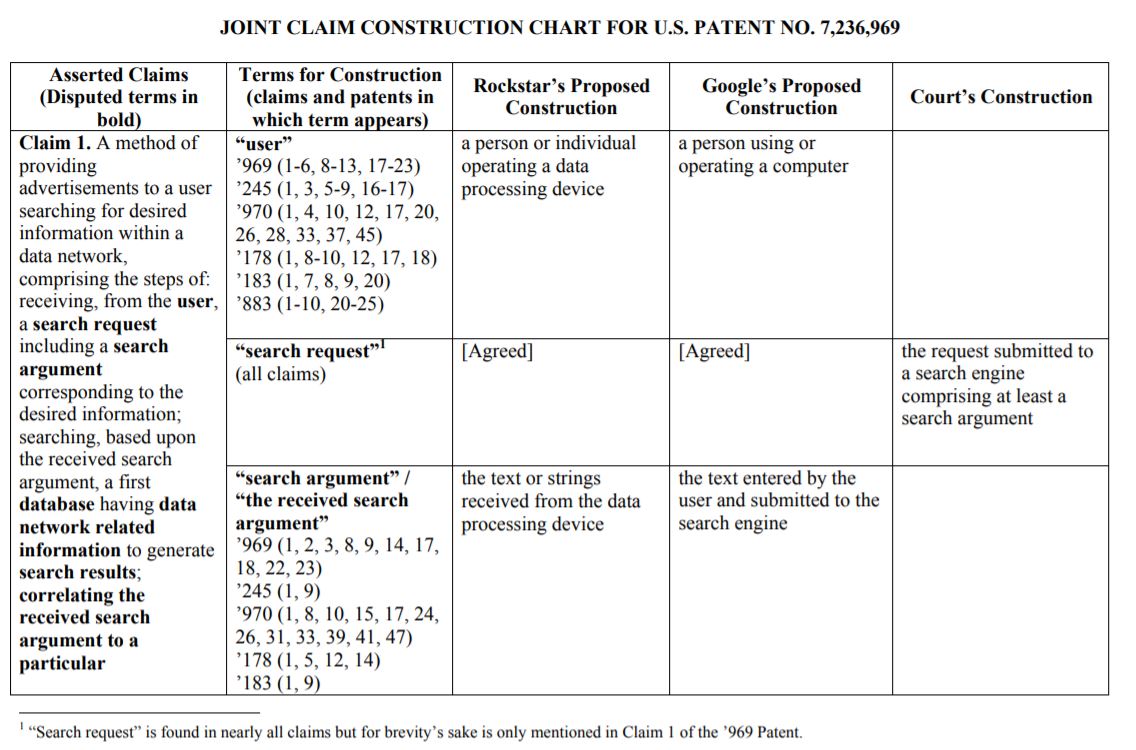

Also, we see a joint claim construction chart when different parties have different interpretations for the claims. As we can see here in Rockstar Consortium US LP et al. v. Google Inc.:

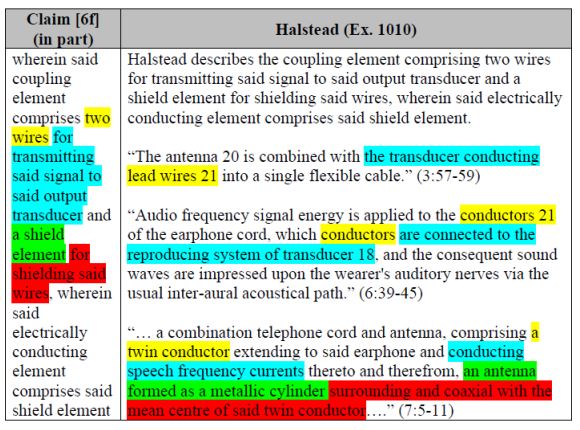

Claim charts are also constructed for various other purposes, such as for reexamination by the PTO during the prosecution stage or PTAB’s review of a patent’s validity. Here we can see a petitioner color-coding to explain each of the components in the claim for a reexamination of the patent:

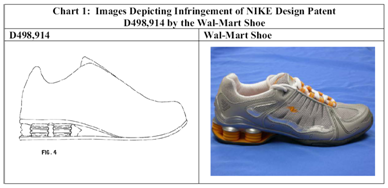

Another example would be to compare designs for design patents. This may not necessarily be comparing the claims, but images, as we can see on the right.

Broadly speaking, claim charts can be used for any purpose regarding patent claim analysis and interpretation.

Conclusion

The matters covered in this article are the general rules concerning patent claim construction, as we still often see disagreements in how to approach claim construction. This is especially true in the U.S., with its case-law system. We can often see discrepancies between the decisions, or lack of decisions in district courts, Federal Circuit Court, and Supreme Court on how to interpret claims. Perhaps, in the future, we may see a more clear and structured method for claim construction in litigation.

Get deeper analyses of patents with Quality Insights and more litigation insights by downloading our white paper — Boundless Patent Strategies: With Invincible Patent Data — From East To West.

Interested in trying our product? Contact us now!