The last article in this series focused on the Preparation Stage: being the step that sets the ground for the whole process, as well as the one in which the overall strategy is mapped out, it is surely the most important. However, a plan can’t unleash its true potential — and value — until it’s executed. This is precisely what happens in the Patent Prosecution Process Stage.

Table of contents

- Patent Prosecution Process: The Stage of Action

- Global Deployment

- How Patent Drafting Impacts Monetization

- Response to Actions

- Continuous Evaluation

- Maintenance

- Download the free white paper

Patent Prosecution Process: The Stage of Action

The Patent Prosecution Process Stage is all about turning the strategy deployed during Preparation into reality.

As we are going to discover in a few minutes, a significant part of this phase also involves managing strategically the patent assets after their issuance.

There are several reasons that make the Prosecution Stage an unmissable step in the overall Patent Lifecycle.

- It defines the future potential of the portfolio

Being the stage that produces the core of the whole process — patents — it directly impacts portfolio performances in the Monetization Stage, setting a baseline for its potential to turn investments into returns.

- It goes hand in hand with Monetization

As we mentioned earlier, the Prosecution Stage doesn’t terminate with the patents being issued but it goes all the way to the expiration of the IP rights into the public domain.

As such, it is tightly connected to the Monetization Stage, especially for what it concerns the Continuous Evaluation and Maintenance steps.

- It is at the center of the feedback mechanism

It is at this stage that patent owners decide whether to maintain or abandon those patents that are not performing well in the Monetization Stage.

Besides deciding whether to keep them active or cease their maintenance, they might even go back to Preparation and adjust their deployment strategy: therefore, it is important for this phase to be flexible and proactive.

Let’s take a look now at the various steps involved in the Prosecution Stage.

Global Deployment

Global deployment starts with invention disclosure.

At this stage, patent stakeholders need to take important decisions to answer the following four questions:

- What type of IP protection — among patent, trademark, copyright, or trade secret — is the most suitable for the invention and its related products or technologies?

- Which technology field, among the many available, is impacted by the invention?

- In which countries should I seek IP protection?

- How does this invention fit in with the existing portfolio, or does it involve a shift in the company’s IP strategy?

Most of the answers to these questions should come from the Patent Prosecution Process Stage, where the deployment strategy has been decided.

The patent applicant, therefore, should simply follow the plan drafted previously.

Oftentimes, however, product or technology planning surveys result in a delay of the actual invention disclosure.

During the time gap, technology landscape and market demands might change, requiring the patent applicant to adjust the strategy before embarking on the Patent Prosecution Process Stage.

Invention Disclosure

Invention disclosures are the direct result of R&D efforts since they closely follow the Eureka moment. Being basically the first notification that an invention has been created, these technical documents establish the new product or technology’s description and define the scope of the future patent. They also detail the reasons why the invention should be worth IP protection, as well as the steps involved in its creation. Drafting an invention disclosure represents the first step into the patenting process.

How Patent Drafting Impacts Monetization

Any patent prosecution process starts with patent drafting.

This phase, by focussing on the claim language, determines the scope of the invention and therefore has a great impact on the patent’s final quality.

Quality patents, in fact, must feature a language that is crafted carefully enough to ensure accuracy and logic, as this will broaden their scope and consequently slim down the chances for competitors to design-around.

Some of the ways in which this stage affects monetization are:

- If the claims are too narrow, the chances to enforce the patent against a third party would be significantly lower as design-around would be a much more feasible option for competitors (for poor quality patents, a company might even be able to implement the invention without infringing);

- Poor drafted claims and specification might eventually lead to a final rejection during the Patent Office’s scrutiny, stopping the development of the patent lifecycle altogether;

- High-quality patents can make it really hard — or even impossible — for competitors to design-around or challenge the patent’s validity;

- Stronger and better-drafted patents have more changes to be used as bargaining chips during selling/buying or licensing activities.

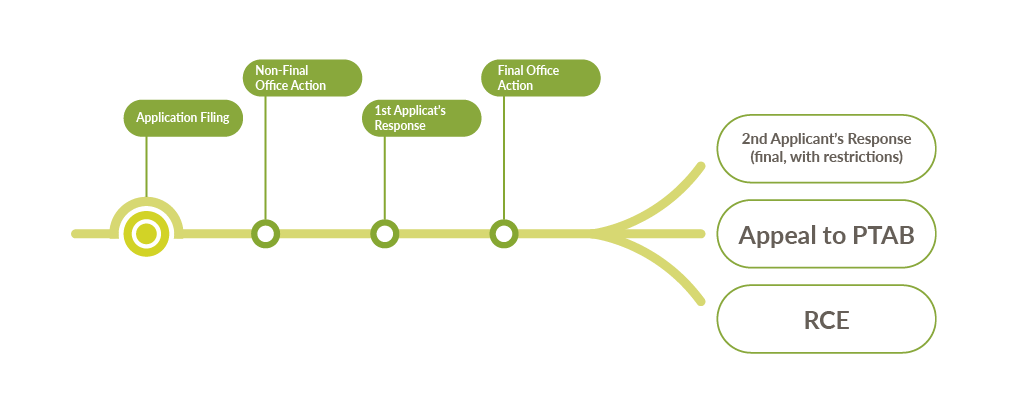

Response to Actions

After filing the application, a back and forth interaction between the Patent Office examiner and the applicant will take place: the Office Actions are the vehicles through which this interaction takes place.

In these documents, mailed to the applicant, the examiner cites the prior art references that he or she uncovered during the patentability check and gives reasons why the claims have been objected or rejected.

In some instances, the issues are not related to the patentability itself, but simply to formal requirements. Patent illustrations are often the subject of such rejections.

Office Actions: Final Vs. Non-Final

- Non-Final Office Actions — These are generally the first office actions received by the applicant. The follow-up steps that the latter can take are:

-

- Reply to the examiner’s objections or rejections and request reconsideration or further examination;

- Modify the claims or the specification to overcome the objections;

- Contact the examiner directly to reach an understanding or clear up possible misunderstandings.

- Final Office Actions — Final office actions generally follow the first applicant’s response. In this case, the options available to the latter are:

-

- Submit a “final” amendment to comply with the requirements set forth by the examiner. To be accepted and evaluated, all the rejected claims must be either canceled or appealed;

- Appeal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB, the former Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences);

- File a Request for Continued Examination (RCE) to keep the examination going. With an RCE, the applicant can amend any claim without the limitations mentioned earlier.

After an Office Action is issued, the applicant has a period of six months for submitting a response.

However, in an attempt to speed up the prosecution process and reduce the Patent Offices’ increasing backlogs, the USPTO introduced a shortened statutory period of between one and three months: responses sent later require the filing of a petition and the payment of a fee.

Office Actions should be submitted by the Patent Office within certain time frames. For more info, read our article about patent expiration dates.

Continuous Evaluation

As mentioned at the beginning, this phase of the Patent Lifecycle is also fundamental for strategic purposes.

In lack of fast frack examination procedures such as the Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) Program, it might take up to 24 months for the Patent Office to issue its first Office Action.

With the PPH Program, applicants receiving a final ruling from a first patent office stating that a claim is allowed can request a fast track examination for that same claim in a corresponding patent application at a second patent office. For the details, visit the dedicated page at the USPTO website.

During this time the inventor’s idea, maybe revolutionary at the time of its inception, might lose its potential from both a technological and commercial viewpoint (for example because it doesn’t satisfy market needs anymore).

This stage, therefore, should include a series of policies and mechanisms to help patent applicants solve the enigma:

Should I keep investing my resources in patenting this idea?

Filing an RCE has its costs. As such, it should be pursued only if the idea to be patented still has potential to generate value: a concept or technology that proves to be surpassed — or not attractive to the market — even before being patented, won’t certainly be profitable in the long run.

This makes even more sense if we consider that the patent being granted doesn’t automatically entitle its owner to enforce it: patents, in fact, must be maintained to be kept in force.

Maintenance

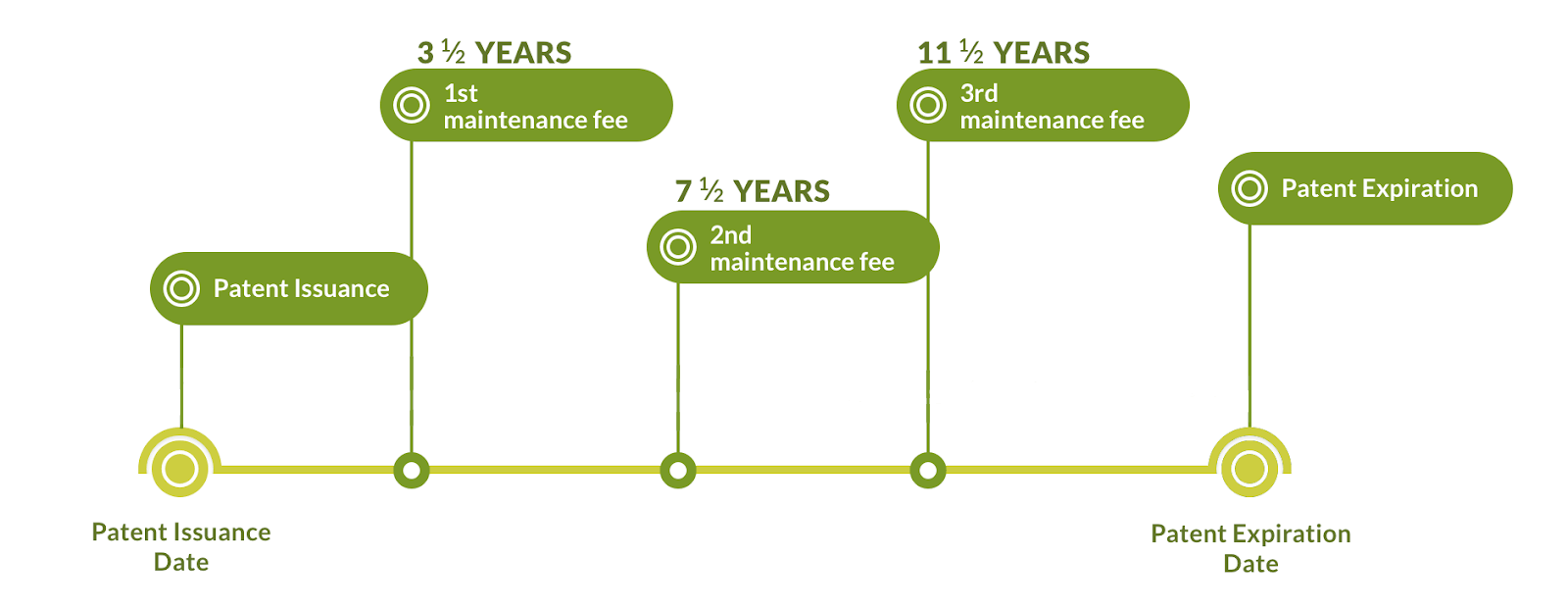

While design and plant patents do not require further investments after their issuance, for utility patents the USPTO provides for three maintenance fees to be paid during the standard term of 20 years from the application date (no fees are due during the pending status):

The payment window opens six months before the due date.

After that, the patent owner has a six-month grace period, during which the maintenance fee can still be paid with an additional surcharge.

Should the patent owner fail to pay the fees before the end of the grace period, the patent will expire for non-payment of maintenance fees and move into the lapsed status.

Patents that are not generating enough value at the Monetization Stage — or that don’t have enough quality to justify their maintenance for strategic advantage reasons — are not worth maintaining, as the costs associated would be too high when compared to the returns.

The importance of the Prosecution Stage should be clear by now: besides providing the raw material — the patents —for the whole process, it also acts as a buffer between the other two main stages, enabling the whole system to be flexible and proactive in case of both external and internal changes.

Dive into the Monetization Stage of patent life cycle, where patents get the chance to generate value.

Download the Free White paper: Patent Life Cycle Management

In this FREE 33-page white paper, you’ll learn:

- Why rethinking the traditional patent investment approach is the key to success

- Why the manual patent valuation process of the past is not effective

- Why managing the patent lifecycle is so important

- The three stages of the patent lifecycle and why they’re critical